Brown Marmorated Stink Bug

Two years ago, one of our contributors wrote about the possibility that the brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) would find its way into Fraser Valley fields—now it’s a reality.

There was some fear about the possible infestation among small fruit growers at that time, but hazelnuts are also at risk as the BMSB damages the kernel itself. Recently, evidence of BMSB has been seen in crops all over the Valley and it’s time for growers to prepare for battle.

At a Pacific Agriculture Show horticulture short course in January 2017, Nik Wiman, Assistant Professor, Orchard Crops Extension Specialist at Oregon State University described the signs of infestation.

“On blueberries, a brown spot will appear on young and mature fruit. The fruit will shrivel and become soft,” he described. “There are also visible salivary sheaths created while feeding.”

“Later varieties of berries and organic berries are at greater risk,” he added. “There is a massive peak in feeding at the end of season. On blackberries, even a small amount of feeding will make the fruit soft and unmarketable.”

Stink bugs also prefer not to feed on fruit that other stink bugs have fed on, so the damage is additive with the most damage occurring at the end of the season.

He also pointed out that it can take a decade from first appearance of the pest until crops are at threat.

“Management will keep their population down,” Wiman assured.

“While researching the BMSB, we measured the chemicals they were putting off [. . .] some are designed to deter birds, others to deter mammals or other insects.”

The odour that the BMSB emits is likened to cilantro. Experiments were designed to mix the stink bugs or the scent compounds with fruit to see how high a concentration was needed before test subjects refused to ingest the fruit puree mixture.

“What we were looking for was what we call the consumer rejection threshold,” explained Wiman. “Blackberry and raspberry puree tests showed that blackberries could tolerate ten times more stink bug contamination than raspberries.”

BMSB’s natural enemies

“You could be the best pest management person in the world and you’d still have a problem with stink bugs flying in from other habitats,” said Wiman. “Tests are done in the field and in the lab to observe what natural enemies the bugs might have. There are few enemies of the adult stink bug, but the eggs are vulnerable.”

Parasitoid wasps will lay their own eggs beside a BMSB egg mass, and when the baby wasps emerge, they will destroy the stink bug eggs. One such wasp from China is being raised and observed in different facilities around the U.S., and considered for wide release to combat BMSB.

While the research was underway, wasps found their way naturally to the West Coast from Korea so researchers received full clearance from federal and state authorities to begin raising these wasps as quickly as they could. Redistribution began in the fall of 2016 to determine how well they survive the winter.

More information can be found online: https://catalog.extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/catalog/files/project/pdf/em9138.pdf

Corn Rootworm

Western corn rootworm is a relatively new pest in BC. There are three main species native to South America which have moved northward over time.

“We are fortunate that we’ve only discovered the western corn rootworm here in the Fraser Valley,” said BCAGRI entomologist, Tracy Hueppelsheuser, at a Pacific Agriculture Show short course.

In 2016, the first confirmed detection of corn rootworm was made in a field of late-planted sweet corn in Chilliwack. When Hueppelsheuser’s team went out to check, they found 3-5 beetles per plant. This launched a survey effort as the team drove through farm land, pulled over and walked the fields to find beetles in Abbotsford, Chilliwack, Matsqui, Sumas, Greendale, Agassiz, and Mission. The rootworm hasn’t been seen yet in North Okanagan or Delta, but it doesn’t mean it isn’t there now.

“This pest is called the billion dollar bug in the States because of the huge costs to growers,” she said. In the States, all field corn is now genetically modified against corn rootworm.

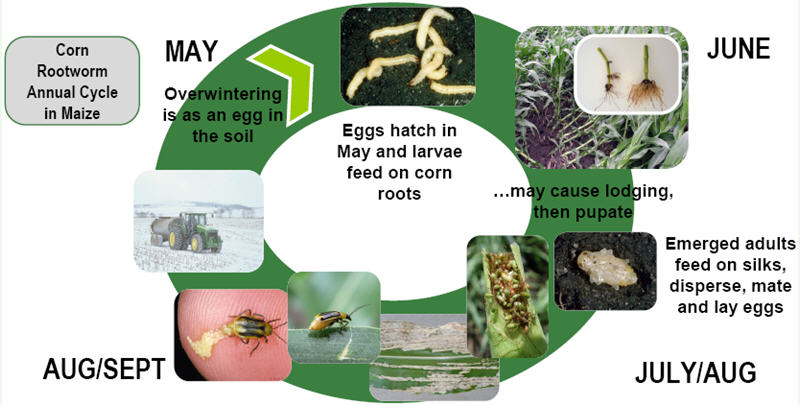

Corn rootworm larvae feed on roots and the adults feed on the upper plant (silks and leaves)—the larvae start out in the soil in the spring. “They could be confused with wireworms, but they have a dark spot on their tail. The larvae cause most damage mid-June to mid-July. They pupate in the soil to emerge as adults in late July. They mate and feed for a couple of weeks, then the females start laying eggs.”

Corn rootworm larvae feed on roots and the adults feed on the upper plant (silks and leaves)—the larvae start out in the soil in the spring. “They could be confused with wireworms, but they have a dark spot on their tail. The larvae cause most damage mid-June to mid-July. They pupate in the soil to emerge as adults in late July. They mate and feed for a couple of weeks, then the females start laying eggs.”

The males are darker in colour and emerge first from the soil and hang around and wait for the stripy female. They don’t travel far, but they are easily disturbed and will fly if they have to.

Any mid-summer flowers are at risk, but the rootworm beetles are partial to cucumbers and melons. Hueppelsheuser mentioned pumpkin flowers might be a good place to observe pest activity. If there are flower farms near the corn, the beetles will likely infest the flowers, affecting esthetics and making the flowers unmarketable.

White striping on the leaves is one indication of activity so this can be used as a monitoring tool. The damage effects pollination so it’s crucial to catch it early.

Another sign to look for is lodging or goosenecking (bending or breaking of the corn stalks) which happens when roots are weakened by the larvae. White roots turn brown or charred looking when fed on.

“Roots were not examined during our survey, but the larvae eat root nodes, so for every node damaged it’s estimated there will be a 15% yield loss. Three nodes of damage is a 45% yield loss—which is very significant,” noted Hueppelsheuser.

Corn rootworm management

“Hand picking is tricky but works to remove the pest,” said Hueppelsheuser, “and sticky traps will help identify them. You can set up a netting system to protect row crops. During August, visual scouting is a good idea, looking for larvae in the soil and checking at least 50 plants per field. Walk the rows and look for beetles, being aware they are easily startled. If you find one beetle per plant on average, you need to plan for management next season.”

“The most effective strategy is to disrupt the life cycle and in this case there is only one generation per year so you only have to break the pattern once,” she confirmed.

According to research in the Midwest and eastern Canada, corn rootworms cannot sustain a population on anything but corn; therefore, crop rotation is the most important management tool.

According to research in the Midwest and eastern Canada, corn rootworms cannot sustain a population on anything but corn; therefore, crop rotation is the most important management tool.

“At least every third year, go out of corn,” Hueppelsheuser advised. “However, every second year is better. At the very least move fields away from each other so they are not adjacent.”

Eggs can be laid as deep as one metre so cultivation is not going to solve the problem. There is some mortality over winter, but it has to be really cold to kill the eggs. Soil covers will keep the beetles out, but coverage must happen early in the year so the timing might not be right. Sandy soil is a deterrent as loamy, moist soil is preferred by the beetles.

Later planting is at a higher risk, so early planting may sustain less damage. Drier soil forces beetles to lay eggs deeper, which will cause more larvae to die on their way back up.

Getting the word out and sharing information is the best way to manage any pest, so as BC farmers learn more about the new pests in their fields, there will be more strategies to pass on.

If you see the pests in areas not surveyed, you can contact Hueppelsheuser through the AGRI plant health unit at [email protected].

Fact sheets and research on pests can be found on many university websites including PennState College of Agricultural Sciences.